Daryna Zadvirna filming in Ukraine.

Author | Carmelle Wilkinson

Watching bombs rain down on her home country of Ukraine during Russia’s invasion was like watching a horror film Daryna Zadvirna couldn’t turn off.

At the time, the Curtin journalism graduate was working as a crime reporter for The West Australian, when she made the bold decision to head to the front line.

“I couldn’t take it any longer. I felt helpless just sitting and watching it all unfold on the TV screens in the newsroom, I just wanted to be there,” she said.

“I wanted to go in any capacity that I could. Whether it was through my profession, or to just go over and volunteer, anything – I just wanted to go.”

In March last year, while millions were attempting to flee the war zones, Daryna took personal leave and headed straight for it.

“The plan was to fly to Poland and then walk across the border. I’m sure many people would have thought I was crazy,’’ she said.

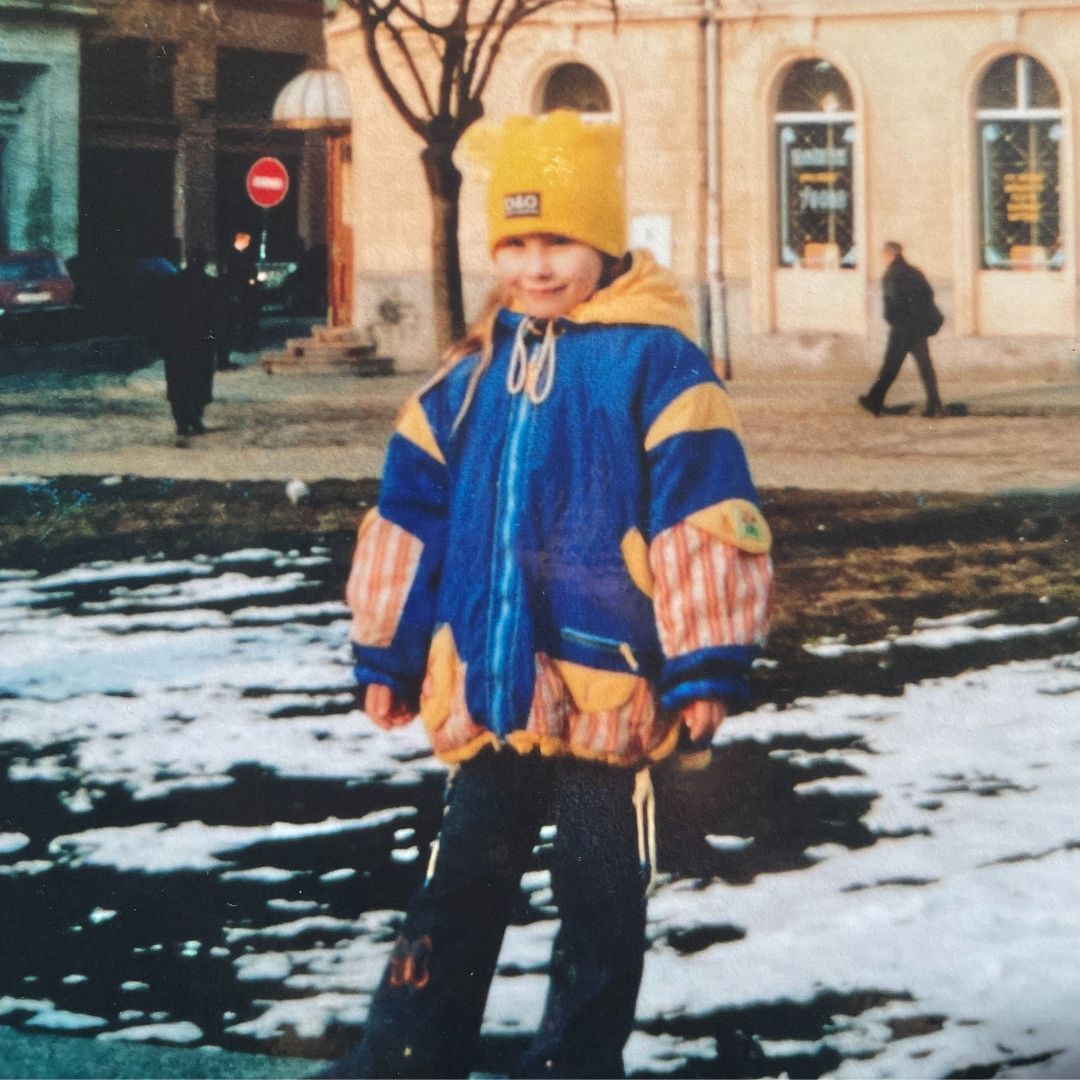

Born in Lviv, Daryna remembers a happy childhood, surrounded by extended family.

A young Daryna.

“When I was 10, we moved to the UK. Mum and Dad both worked in the medical profession, but funny enough, I was never interested to follow in their footsteps. Medicine just wasn’t for me,’’ she said.

“I loved writing stories and poetry, so I guess it’s no surprise I ended up studying journalism.”

Armed with a backpack, camera and note pad, Daryna spent five weeks travelling through Ukraine, sharing untold stories from those on the frontline.

Unlike other foreign media, she would do it without an entourage, bodyguards, driver, or translator.

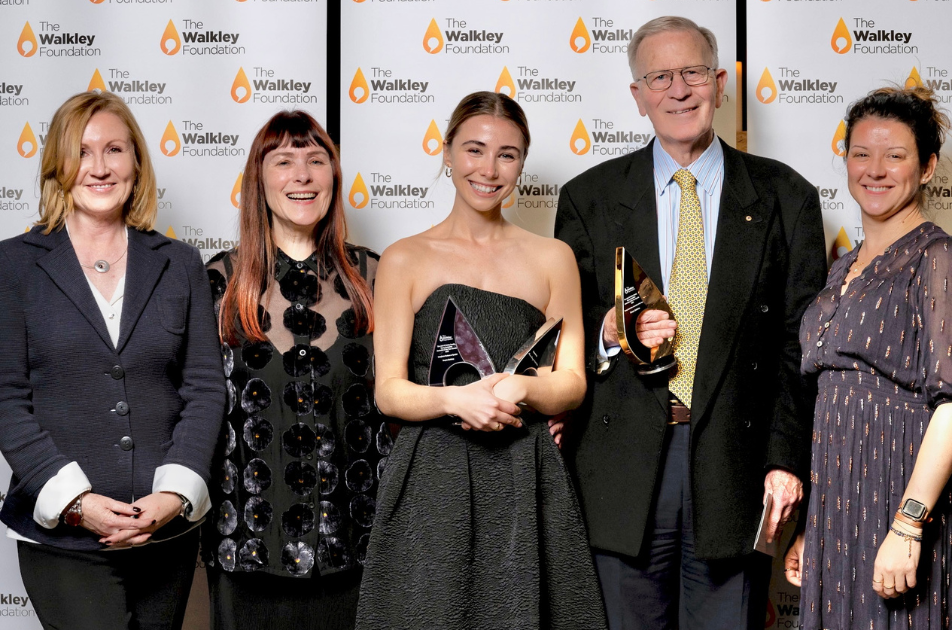

Her award-winning documentary My Ukraine: Inside the Warzone, received both local and national acclaim and earned the now ABC cross-platform reporter a prestigious Walkley Award for Young Australian Journalist of the Year.

Daryna (centre) at the Walkley Foundation young journalist of the year awards earlier this year.

Daryna said while she learned to emotionally distance herself from trauma and tragedy when she worked as a crime reporter for The West, nothing could prepare her for what awaited in Ukraine.

Images L-R: Children on the street in Bucha and a woman, who saw her son-in-law shot in the street, walks past a blown-up Russian tank. Credit: Daryna Zadvirna.

“I can only describe it as genocide,’’ she said.

“I still have nightmares.”

Daryna said one of the hardest things to witness was the huge loss of life.

“When you’re watching the war on TV, you’re seeing smouldering ruins, heavily armed soldiers walking the streets and mass groups of people fleeing danger. You don’t see the mass graves, children starving in the basement of their homes or the torture chambers,’’ she said.

“There are dozens of Ukrainian faces seared into my brain: the woman who saw her son-in-law shot on the street but couldn’t move his body because she’d suffer the same fate; the people who had to bury children; the mothers waiting outside the surgery room waiting to find out if their wounded children would survive and a four-year-old Mariupol girl too traumatised to speak.

“And then there are the faces of those whose stories are too morbid to tell.”

Daryna said one the more horrific sides to the war, happened in Butcha.

“I’m not sure why this wasn’t covered widely by mainstream media, but there were reports from neighbours and relatives of women and children being brutally raped and tortured by the Russians,’’ she said.

“Publications like the New Yorker picked up the story, but for the most part, everyone just glazed over this. They seemed more interested in covering the sensationalism of war.”

Arriving at Ukraine border in the middle of the night, Daryna was questioned for over an hour before being allowed to enter.

“Most people were leaving Ukraine, not many were trying to get in, so they wanted to know what I was doing,’’ she.

“My aunt and uncle were waiting for me on the other side of the border, and after I passed security we drove back to their place in Zhovka, a town near Lviv.

“The drive home was unusually quiet. Normally we’re chatting away and catching up, but this time was different. The ride was mostly silent, except for the radio which provided regular updates on the number of casualties and road closures.”

Over the next five weeks, Daryna would travel through Ukraine by train and volunteer/humanitarian trucks to the country’s recently liberated towns.

Daryna and a group of people from a small village near Kyiv (which had been liberated from Russian occupation).

“Everyone was so nice and helpful. I didn’t spend one night in a hotel,’’ she said.

“I mostly stayed with friends of family, or friends of friends, and in the end just complete strangers.”

Daryna said every other day a local man who decided to go to war would return in a casket and the whole community would gather to pay their respect.

“It was like a collective grief, everyone was feeling it,’’ she said.

Daryna said the emotion with which the Ukrainians told their stories gave her the strength to follow through and share their stories.

“I didn’t really grasp what was actually happening around me until I landed back home in Australia,’’ she said.

“In Ukraine I was in full work mode, so never allowed myself to get too swept up in it. But looking back now, I wish I had stayed longer.”

Daryna said sitting with families in the basement of their homes as they armed themselves with frying pans and shovels, was a reminder of her of the true character of the people of Ukraine.

“Out of all this tragedy, horror and grief they had an enormous amount of resilience, resistance and grit despite what was happening around them,’’ she said.

“It’s come at a huge price but now the world has seen Ukraine for what it is. I like to think we’ve earned the respect of people and leaders around the world.

“Putin’s invasion has had an opposite effect of what he intended. He’s made Ukraine a stronger country.

“I hate to see the world lose interest or forget what’s happening. But there is not a shred of doubt in my mind that we will come out of this better and stronger in the end and we will win.”

Daryna’s powerful documentary shows the world the grit, resilience and unwavering strength of Ukranians.

It’s this same grit and fighting spirit, which gives Daryna the confidence and thick skin to navigate the world of journalism.

“Those first few months following graduation weren’t easy, but you do adapt,’’ she said.

“My advice would be to listen intently to your senior journos and editors around you. Take their advice, but also stay true to yourself and learn to say no when something doesn’t align with your moral compass.

“Always remember the true purpose of the story you are telling and treat people as you would want to be treated.”

Now a cross-platform reporter for the ABC, Daryna is passionate about covering stories that change, shape and impact lives.

Watch Daryna’s award-winning documentary, ‘My Ukraine: Inside the Warzone’ here.

Author | Carmelle Wilkinson

___