The moon may be the key to unlocking how the first stars and galaxies shaped the early Universe.

A team of astronomers led by Dr Benjamin McKinley at the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) and the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) observed the moon with a radio telescope to help search for the faint signal from hydrogen atoms in the infant Universe.

“Before there were stars and galaxies, the Universe was pretty much just hydrogen, floating around in space,” Dr McKinley said.

“Since there are no sources of the optical light visible to our eyes, this early stage of the Universe is known as the ‘cosmic dark ages’.”

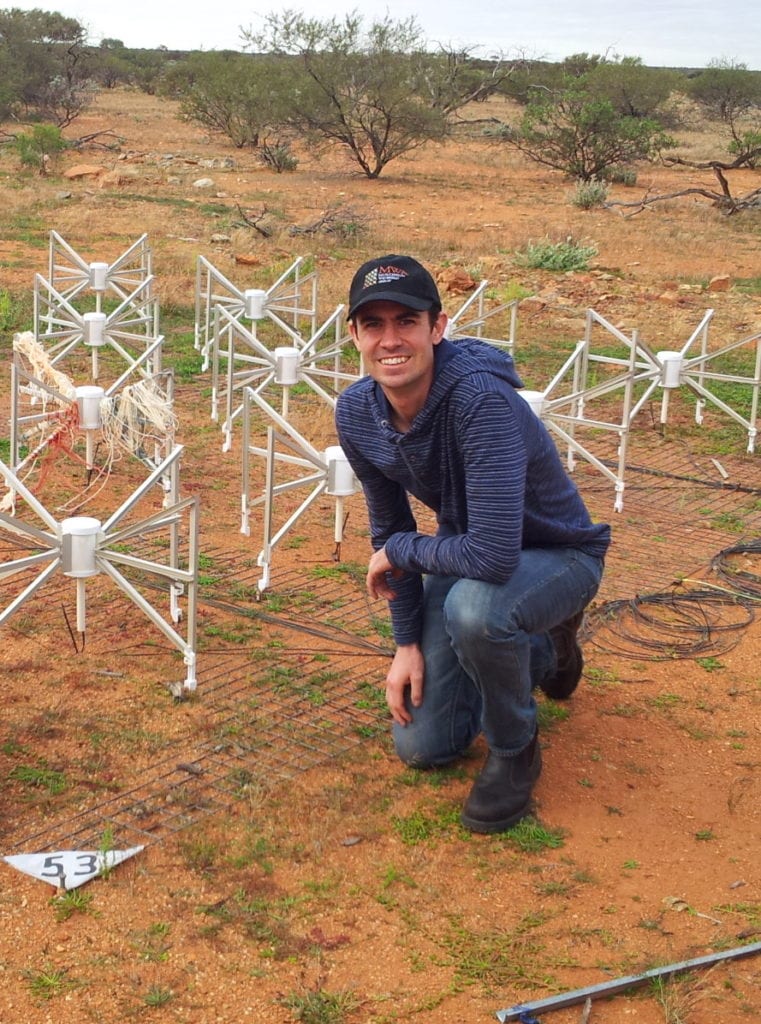

In research published in the Oxford University Press Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society today, the astronomers describe how they have used the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) radio telescope, in the Western Australian desert, to help search for radio signals given off by the hydrogen atoms.

Dr McKinley said that if these radio signal are able to be detected, it will reveal whether existing theories about the evolution of the universe are correct.

“A car radio can tune in to various channels and the radio waves are converted into sounds. The MWA takes the same radio channels and converts the information into images of the sky,” Dr McKinley said.

“This radio signal from the early Universe is very weak compared to the extremely bright objects in the foreground, which include accreting black holes in other galaxies and electrons in our own Milky Way.

“The key to solving this problem is being able to precisely measure the average brightness of the sky. However, built-in effects from the instruments and radio frequency interference make it difficult to get accurate observations of this very faint radio signal.”

The astronomers used the moon as a reference point of known brightness and shape, which allowed them to measure the brightness of the Milky Way at the position of the occulting moon.

The astronomers also took into account ‘earthshine’, which are radio waves from Earth that reflect off the moon and back onto the telescope.

Earthshine corrupts the signal from the moon and the team had to remove this contamination from their analysis.

With more observations, the astronomers hope to uncover the hydrogen signal and put theoretical models of the Universe to the test.