The power of Hoda Afshar’s talent and the intellect that infuses her art is giving Afshar a cumulative following across Australia. Her desire to understand marginalisation has also led to her undertaking a PhD in Creative Arts at Curtin.

Afshar left her home town of Tehran 11 years ago, already a respected photojournalist and artist. In fact, in 2006, World Press Photo acknowledged her as one of Iran’s top young documentary photographers. She arrived in Sydney in 2007, imagining Australia to be a liberal-minded, progressive country, but became increasingly perplexed by the discourses surrounding immigration.

“One thing I noticed was that mainstream images, particularly in the media and contemporary art, seemed to be supporting practices of marginalisation. This led me to search for the roots of these representations,” she explains.

“I began studying western representations of Muslim women, partly in response to my own experience, and ‘veil art’ in particular.”

The shifting frames of veil art

She coined the term ‘veil art’ to describe the mainstream representations of the veil worn by Muslim women. While western depictions of the garment have always signified ‘otherness’, she points out that colonial representations (the male viewpoint) of the veil were curious and fetishised: the enigmatic female; beautiful harem dwellers, spirited but docile.

“But after 9/11, the veil came to represent a threat. And recently there’s been another shift, with the veil now symbolising oppression. And something archaic.”

Ironically, she explains, these representations inadvertently strengthen the concept of white-male chivalry – the quest to liberate the disempowered and the persecuted.

“It supports an assumption, particularly in feminist discussion, that all female Muslim immigrants are escaping oppression.”

Realising that the paradoxes in images of oppression and marginalisation in Australian media and art warranted formal research, Afshar enrolled in a Master of Philosophy at Curtin, shortly after moving to Perth with her then partner. She then extended her research into a PhD project.

“Half of my project is a written thesis, the other half is a creative production that confronts the discourses around migration and identity.

“These are complex issues and a challenge to portray. But you gain a greater understanding in a PhD, and the deeper level of inquiry helps to refine your creative production.”

Beneath the oppression: incarceration on Manus and freedom in Behold

Now based in Melbourne, Afshar visited Perth recently to present her internationally acclaimed exhibition Behold. The work provides an exceptional glimpse into the existence of gay men in a Middle East city. As far as she’s aware, her images are the only documentation of the historic bathhouse where the men used to meet (the building has since been destroyed).

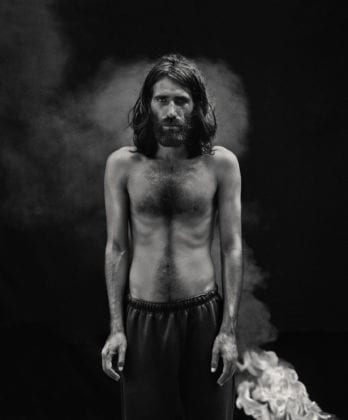

While her focus differs markedly from her previous works, Behold sits firmly in Afshar’s tradition of revealing the covert defiance behind overt oppression. Still, the quiet happiness she captures in Behold contrasts with the human fatigue she encountered on Manus Island – the setting of her famous photograph of Behrouz Boochani, a well-known asylum seeker and writer who’s been in detention since 2013.

Afshar won the 2018 Bowness Photography Prize for her portrait of Boochani, which was part of a creative collaboration with several Manus Island refugees; however, she didn’t arrive in Papua New Guinea as a photographer, with a camera over her shoulder.

“I would have been barred from Manus if I’d declared my reason for visiting,” she says. “I entered as a tourist, but as soon as it was obvious I was a photographer I was being followed – I even had immigration officials hanging around my hotel window.”

She spent 10 days on Manus Island, working closely with the refugees in small groups (all the while being followed by officials).

“Most of the detainees are fragile, the majority seem broken. Behrouz is different. He trained as a journalist in Iran so he understands the power of communication, and he was able to get news out of Manus when nobody else could. Writing gave him purpose and resolve.”

To avoid scrutiny, Afshar travelled with Behrouz Boochani and his friends 40 minutes by dinghy to a small island owned by a Papua New Guinean man and his family.

“It is one of the few places on Manus where detainees can escape for a few days at a time. The family are beautiful people – they welcome visits from the asylum seekers. They even helped build a makeshift studio for me out of poles and robes,” she says.

The collaboration resulted in a multi-channel video installation and a series of portraits, from which she selected an image of Boochani to enter into the Bowness competition. She recalls his shock when he first saw the photo.

“He said it scared him. He said, ‘It’s me, but I do not see myself in this picture. I only see a refugee … a bare life standing outside the borders of Australia, waiting and staring’.

“He was looking at his own image through the eyes of the beholder and thinking how his stare would make the audience feel.

“But Behrouz is actually a hopeful man. He has a passion for life, and, although he’s been in detention for years, he still has a sense of innocence and peace.”

Praising the portrait as having ‘immense visual, political and emotional presence’, the Bowness judges awarded Afshar the $30,000 first prize.

Trust in the power of art … and the app

In a brilliant complement to Afshar’s Bowman Prize, Boochani himself recently won the Victorian Prize for Literature – Australia’s richest literary prize, no less – for No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, a 400-page memoir built by What’s App messages from Boochani to his translator in Australia.

Afshar attended the Melbourne event where No Friend But The Mountains was announced as the winner, and sent Boochani a video of the ceremony.

“His prize is a huge victory – it gives all of us hope,” she says.

And on her own success, she says that winning the Bowness Prize for the portrait of Boochani was a glorious moment in her career.

“It is also a confirmation of the trust that I’ve always placed in the power of art to change the world, through changing the way we see it.”

Afshar is currently working on her thesis, which is sure to reveal more about the power of art.