For most of us, the ‘final frontier’ is only accessible by immersing ourselves in a science fiction book, film or television series. But that doesn’t apply to a Curtin mechatronics student, whose designs for a smartphone-sized robot could be used on future missions by NASA to locations such as Mars, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Chris Norman recently took part in a six-month internship at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) – a research facility based in Pasadena, California that conducts cutting-edge work in Earth science, planetary exploration and technology development.

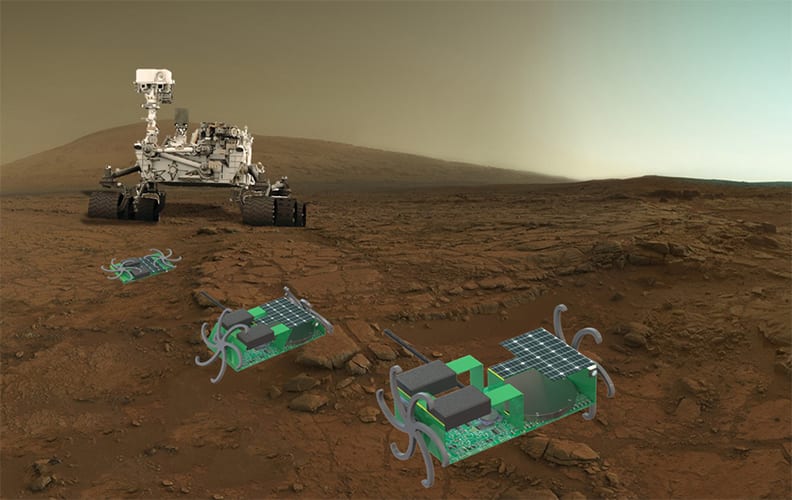

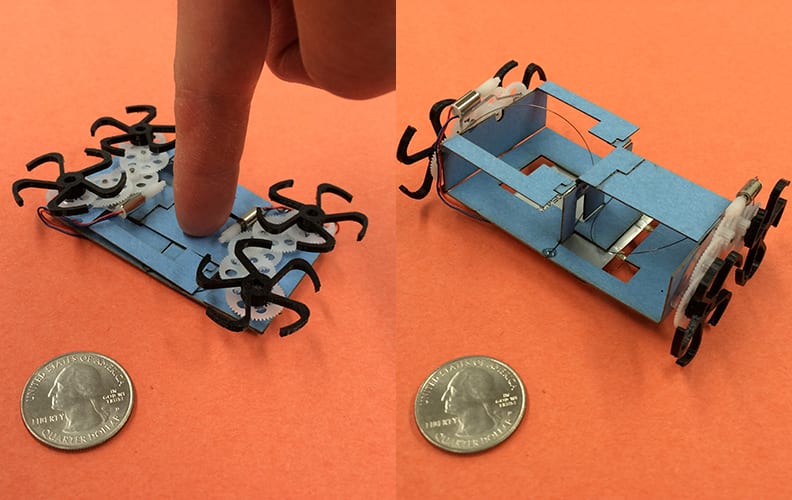

Norman primarily spent time on JPL’s PUFFER (Pop-Up Flat Folding Explorer Robots) project, where he was tasked with helping to design the physical components of diminutive pop-up robots that will eventually be sent to drive across alien terrains inaccessible to larger rovers.

“Basically, the concept is that instead of having a suite of instruments, like the Curiosity rover [stationed on Mars], which costs billions of dollars, you downscale and only include one or two instruments, plus a temperature sensor, radiation sensor and camera,” says Norman.

“Part of the advantage of having it unfold and fold is that when it takes a bit of a drop, it’s able to collapse in on itself and take the impact. To an extent it’s like suspension in a car.”

Norman worked in a team alongside five “super casual” and “really passionate” t-shirt and shorts-clad JPL engineers, who designed other elements of the pop-up robot, such as the electronics, circuit boards and folding structure.

“I used modelling software to create the parts I needed, and they would come out of a state-of-the-art 3D printer within two hours. Then I’d take them, clean them, test them and fit them against the rest of the structure. I had to turn out designs really quickly,” says Norman.

“Being around people so successful pushed me to succeed. Everybody had their masters or PhDs – they were incredibly, incredibly knowledgeable and self-driven – and the way they tackled [seemingly impossible] problems astounded me.”

Norman would also prepare the robots for the cold environment on Mars, placing the components in an oven-like liquid nitrogen tank, which was “preheated”, as he jokingly describes it, to -135°C to see how they performed during extreme drops in temperature.

“The internship felt totally surreal to me even when I was over there. Honestly, there wasn’t a day that passed where I didn’t think, ‘Wow, this is absolutely incredible’,” says Norman.

Working a 9/80 Work Week – 80 hours over a nine-day period – might have been exhausting for some, but it was ideal for Norman, who used the extra day off to take part in activities, such as exploring California’s beaches and snowboarding at its mountains, which allowed him to better connect with the JPL staff who accompanied him.

Now, settling into Perth life, it’s back to business for the fourth-year Curtin student, who will continue his engineering studies and begin a thesis project, which will involve writing a program to detect the location of craters in high-resolution images of Mars.

“Everything I’ve learnt during my classes, like the technical skills and the practical project work, has been really, really good. Instead of just sitting in the classroom, we’re spending six to ten hours a week in the labs, actually doing projects, building robots,” Norman says.

After completing the internship, Norman has now decided that he will move towards innovative research and development work in engineering in the future.

“I’d love to work on projects and ideas that are brand new and fresh. Whether they end up being sent to space or remain on Earth doesn’t matter,” he says.